Global Warming: Huge carbon dioxide sinks could change the climate on Earth

Reducing the planet's temperature by massively reducing the presence of carbon dioxide from the air will require thousands of new environmental stations around the world, but what do they need to achieve their goals?

Imagine that in the year 2050, you emerge from an oil museum in Midland, Texas, and head north through the sweltering desert dotted with a few pumps of oil wells under the blazing sun, before you appear in front of you a gleaming palace rising among the flatlands. The land is covered with vast photovoltaic panels stretching in all directions, intersected in the distance by an enormous gray wall of five floors and stretching for a kilometer. Behind the wall, you can glimpse the winding pipes and towers of a chemical processing plant.

If you approach the wall, you will see it moving and sparkling. This wall is composed of huge fans inside boxes of steel. You might imagine that it is a giant air conditioner, inflated to extraordinary dimensions. And you may be right.

This wall is a direct air carbon dioxide capture station, one of tens of thousands of similar stations around the world. Combined, these plants may contribute to cooling the planet by pulling carbon dioxide out of the air.

In the twentieth century, this region of Texas attracted attention after billions of barrels of oil were extracted from the depths of the earth. Now the carbon dioxide left over from oil extraction is drawn from the air and released back into the empty oil reservoirs.

Skip topics that may interest you and continue reading. Topics that may interest youtopics that may interest you. End

We may now need these stations around the world if we are to meet the Paris Agreement targets of limiting global warming to 1.5°C by 2100.

But back in 2021, in Squamish, British Columbia, Canada, the finishing touches are being put to a barn-sized device covered in blue tarpaulin against snow-capped mountains amid green farms as far as the eye can see. The prototype direct-to-air carbon capture plant developed by Carbon Engineering, a clean energy company in Canada, is scheduled to go online in September, after which it will start pulling a ton of carbon dioxide out of the air annually. Another, larger plant is under construction in Texas.

Skip the podcast and read onMorahakatyTeenage taboos, hosted by Karima Kawah and edited by Mais Baqi.

The episodes

The end of the podcast

Steve Oldham, CEO of Carbon Engineering, says: “The climate change crisis is caused by the high concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and carbon capture plants directly from the air may contribute to removing any emissions produced anywhere and at any moment.” .

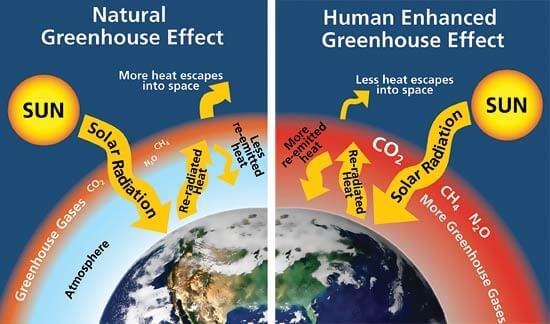

Most greenhouse gas capture devices are used to purify emissions at the source. Scrubbers and filters are placed on stacks to prevent harmful gases from reaching the atmosphere. But these devices are not practical with small emissions sources such as cars, which may number on the surface of the planet close to a billion cars. Nor will it work to draw in carbon dioxide that's already in the air. Therefore, the most effective alternative is direct air carbon capture plants.

It may also not be enough to build carbon-neutral societies to protect us from the catastrophic consequences of climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned that limiting global warming by 1.5°C by 2100 will require the use of technologies such as direct air carbon capture to eliminate large-scale carbon dioxide disposal. This means removing billions of tons of carbon dioxide annually.

Elon Musk recently pledged $100 million to build carbon dioxide capture plants from the air, while companies such as Microsoft, United Airlines and ExxonMobil are investing more than $1 billion in projects in this field.

"According to current statistics, we will need to remove 10 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide annually by 2050, and this number will double by the end of the century. And at the moment we are not eliminating any emissions at all," says Jane Zelikova, a climate scientist at the University of Wyoming.

The Carbon Engineering plant in Squamish was designed as a testing ground to test various technologies in this field. But the corporation plans to build a larger plant in the oil fields in West Texas to remove one million tons of carbon dioxide annually. But Oldham does not deny that they still have a huge task ahead of them.

Creative ideas

There are many ways to capture carbon directly from the air, but the system developed by Carbon Engineering relies on fans to extract air containing 0.04 percent carbon dioxide and then pass it through a filter saturated with a potassium hydroxide solution, which is known as Caustic potash. Potash absorbs carbon dioxide from the air and then passes through tubes to a second chamber, where it mixes with calcium hydroxide, which is called slaked lime.

The lime captures the dissolved carbon dioxide to produce flakes of limestone, which are heated in a third chamber, called a calcining kiln (or rotary kiln), until it decomposes and releases pure carbon dioxide, which is captured and stored. This process does not produce any waste, as all remaining chemicals are recycled in the subsequent steps.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has presented some models to keep the global temperature from relying on capturing carbon dioxide directly from the air. But Ajay Gambhir, a senior research fellow at University College London's Grantham Institute for Climate Change who co-authored a paper in 2019 on the role of carbon capture from the air in mitigating climate change, finds it unrealistic in its assumptions about energy efficiency and people's willingness to change their behaviour. .

Alternative ways to remove carbon from the air naturally include land-use change, such as peatland restoration or tree planting. But changing land use would take a long time to remove the required amounts of carbon dioxide and would require planting trees on vast tracts of farmland, the size of the United States, by some estimates, and could raise food prices fivefold. When these trees die, they release the carbon that was stored in them, unless they are cut down and burned in an enclosed facility.

However, direct carbon capture plants also present significant challenges. Gambhir's study concludes that we may need to build 30,000 large direct-air carbon capture plants to keep up with global carbon dioxide emissions, which currently stand at 36 gigatonnes per year. The cost of building each station amounts to 500 million dollars, meaning that the cost of building all stations amounts to 15 trillion dollars.

This fleet of stations, sufficient to sequester 10 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide annually, would need about four million tons of potassium hydroxide, which is one and a half times more than the annual global supply of this chemical.

Once these plants are built, they will require electricity to operate. "If plants were built worldwide to absorb 10 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide annually, they would consume 100 exajoules of energy, about one-sixth of the total energy consumed globally," Gambhir says. Most of this energy will be used to heat the calcining kiln to 800°C.

The cost of emissions

It is estimated that the cost of capturing one ton of carbon dioxide from the air may range between 100 and 1000 dollars, but Oldham confirms that the "Climate Engineering" company can sequester carbon at a lower cost that may reach $ 94 per ton, especially if this spread stations widely.

But another problem is financing carbon sequestration. Air carbon capture produces a valuable commodity: thousands of tons of compressed carbon dioxide, which can be added to hydrogen to make carbon-neutral synthetic fuels. This fuel can be sold or burned in calcining kilns, where the carbon dioxide can be captured again and the same process repeated.

However, surprisingly, compressed carbon dioxide is a popular commodity in the oil sector. When a well is about to run out, oil companies try to extract the remaining oil by pressing down on the oil reservoir using steam or gas in a process called enhanced oil recovery.

Carbon dioxide is a common option used for this purpose, and this process has the added advantage of storing the carbon underground. Occidental Petroleum, which partnered with Carbon Engineering to build a direct air carbon capture plant in Texas, uses 50 million tons of carbon dioxide per year in its enhanced oil recovery operations. The company also gets a tax deduction equivalent to $225 for each ton of carbon dioxide used for this purpose.

In this way, the carbon dioxide will be returned to the oil fields that resulted from it, although the irony is that the only way to finance this process would be to produce more oil!

Occidental and others hope that pumping carbon dioxide underground will reduce the oil sector's share of greenhouse gas emissions.

There are other profitable uses for carbon dioxide. The Swiss company Climawerks owns 14 smaller air-to-air carbon capture units, which capture 900 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year and sell it to a greenhouse to improve the growth of vegetables used in making pickles.

The company has launched a project to set up a station in Iceland to mix the captured carbon dioxide with water and pump it at a depth of 500 or 600 meters underground, so that the gas interacts with basalt and turns into rocks. This station is funded through a website to allow companies and citizens to pay monthly subscriptions to finance the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, starting at 7 euros per month.

Of-air carbon capture plants are expensive, and there is no financial incentive to get them up and running,” says Chris Goodall, author of The Steps We Should Take Now: Towards a Zero Carbon Future. Through environmental contributions, contracts with Microsoft or encouraging people to fund removing tons of carbon dioxide from the air through Stripe.

Governments do not currently support financially projects to extract carbon from the air, as much as they support projects to deploy electric cars or establish solar power plants. The focus is on reducing emissions and not on removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which represents A big part of the problem."

Zelikova believes that the cost of direct air carbon capture plants will decrease over time, like other devices and technologies developed to address climate change. She says, "We have faced similar obstacles when setting up power plants from wind and solar energy. This obstacle can be overcome by spreading their use as much as possible."

Goodall calls for a global carbon tax, to double the cost of producing greenhouse gas emissions. But he believes that this option will not be welcomed, as no one wants to bear more taxes, especially if people do not recognize that extreme environmental phenomena, such as forest fires, droughts, floods and sea level rise, are reflections of our excessive energy consumption.

risks and rewards

Assuming we build 30,000 direct air carbon capture plants, and provide the chemicals to operate them and the money to finance them, some of these plants may be used as an excuse to abandon carbon reduction measures.

If you rely on air capture plants in the long or medium term, we may underestimate carbon emissions reduction measures, Gambhir says. or more costly than expected, abandoning carbon emissions reduction measures may make it impossible to limit global warming.

For opponents of air carbon capture, the technology has been widely welcomed simply because it allows people to continue their usual carbon-emitting lifestyles. But Oldan believes that the use of carbon capture plants from the air in some sectors that are difficult to reduce carbon emissions resulting from, such as aviation, may be the best solution to remove the emissions caused by these sectors.Reducing the rise in global temperatures will require rapid reductions in carbon emissions while building plants to remove carbon from the air, Gambhir said. Zelikova says that CCS will play an important role, along with emissions reduction measures, in removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

For Oldham, the biggest challenge to deploying direct air carbon capture plants on a large scale is proving that they are "feasible, low-cost and feasible". Perhaps if Oldham scales up the Carbon Engineering project to capture carbon from the air, the fate of the planet's climate will once again be determined by the Texas oil fields.